Front Matter

In his introduction to the new 40th-anniversary edition of The World According to Garp, John Irving writes about handing a manuscript of the novel to his 12-year-old son to read. “There are scenes that are unsuitable for twelve-year-olds,” he writes. True enough: There’s lots of sex and violence, and lots of violence framed as a consequence of sex. But as somebody who read Garp at around the same age, I’m here to testify that I escaped pretty much unscathed.

I’m at a loss now to remember why I picked up the book. I was 11; the film version starring Robin Williams was on video, or cable; I watched a lot of TV, so it was definitely in the air. What I wasn’t doing much back then was reading books; in grade school the lion’s share of my experience with literature was consumed by SRA cards. (Which unwittingly introduced me to Raymond Carver, maybe.) But for whatever reason, I went to a bookstore and bought a cheap paperback copy of Garp, and nobody suggested I wasn’t ready for it. The book accompanied me on a long road trip from Chicago to Cleveland to visit relatives---none of whom suggested I wasn’t ready for it---and I spent a lot of time in my guest bed reading Garp and learning about literary ambition and antifeminist rage and transsexuality and the bad things that can happen when you use a car in a driveway for a hookup. I could only have been identified during family gatherings that weekend in Cleveland as the fat kid who couldn’t get his nose out of The World According to Garp.

I don’t remember too many books as experiences in themselves, but Garp left a strong impression---it was the first grown-up book I read all the way through, and I cherished it because I figured there was a lot of truth-telling in it. Here was stuff that a preteen wasn’t going to learn about in the real world without the most sensitive and responsible guide imaginable. (And even then, the idea is pretty squicky.) I don’t dare read it again, because doing so would only break its spell; I’d also probably find a lot of it trite. But it’s the book that made me feel that writing was interesting, and that being a writer might be an interesting to be.

So Garp was a net benefit, even if it wasn’t age-appropriate. But what’s “age-appropriate,” exactly?

I have an 8-year-old son. Eight is an interesting age for a reader; it’s a time of transition into chapter books, sustained plots, and characters with at least a passing acquaintance with complexity. It is a substantial joy as a parent to finally escape the “I Can Read!” era. But this time is also, as Idra Novey thoughtfully pointed out in a recent New York Times piece, when young boys are condescended to with books filled with poop jokes and anti-authority snark. I’ve declared a household moratorium on Captain Underpants books, not because I feel insecure in my role as a parent; I’ve done it because they’re exasperatingly one-note and tedious. (Jeff Kinney’s “Diary of a Wimpy Kid” series has a little more wit in it, but that so-called underdog has a fair bit of cruelty in him, and the movies are awful.)

So I’m gratified, pace Novey, that my son also adores Charlotte’s Web and is enchanted with Kate DiCamillo’s novels; some of my most pleasurable reading experiences of the past month or so were hitting the home stretches of Because of Winn-Dixie and The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane. “What children read at this point can influence how they respond to the pressure to conform to type, and whether they impose that pressure on others,” Novey writes, which rings true. The tricky part with an 8-year-old---and perhaps with any reader---is that he smells Adult Guidance from a mile away, and, bless him, endeavors to resist it.

Novey describes no strategy for that, and I don’t have one to share either. Except to say that you can’t be direct about it; aggressively pressing a book into somebody’s hand isn’t in my nature, either as a parent or as a critic. If he’s reading, I figure, don’t intervene. (Except with Captain Underpants.) My son once spent a month seemingly interested in reading nothing but a two-volume bird guide; he also occasionally grabs a random novel ARC from my stack and reads the first couple of pages before giving up. (Perhaps there’s a lesson there.) I didn’t inflict Charlotte’s Web on him; I just kinda kept it around his bookshelves. DiCamillo he found on his own library searching. The stuff you truly love is the stuff you stumble over. So I’m taking Novey’s recommendation and putting Grace Lin’s Where the Mountain Meets the Moon in his Christmas stocking. (Don’t tell him.) But that’s just me doing half my job as a parent; the other half of the job is letting him feel like he found it all by himself.

What I’m Reading, Essay Dept.

Alex Abramovich rightly praises John McPhee, though the book under review, The Patch, is a bit of a hash, and its intentionally being so makes it no less of one. Mychel Denzel Smith voices his frustration with a media culture that persistently recruits black writers to explain black culture to white readers. I wish I had the feel for Elena Ferrante that so many readers seem to have; I’ve read the first and final volumes in her Neopolitan Quartet and found them...OK, I guess? Regardless, Rachel Donadio’s exploration of Ferrante’s true identity is less a literary whodunit than a look at what assumptions we bring to a writer. Marie Myung-Ok Lee on the hellscape of blurbing today.

What I’m Writing

At On the Seawall, which has become a lively repository of new poetry and literary commentary, I cover two newly released books by Lucia Berlin, who’s enjoying a posthumous career revival. I’ve used that as an opportunity to comment a little on the revival itself, and the curious pigeonholes that fiction writers are often thrust into: “Both books reveal a titanic anxiety about her standing that makes it hard to turn her into a type. Her characters crave domesticity but also chafe at it. She wrote about motherhood but seemed to find no particular fascination in it as a subject. She wrote often about place — she’s especially expressive about New Mexico — but didn’t settle long enough in one place to fully claim one perch in particular. Ultimately, she was a writer about disconnection of multiple sorts — an ambassador without an embassy.”

End Notes

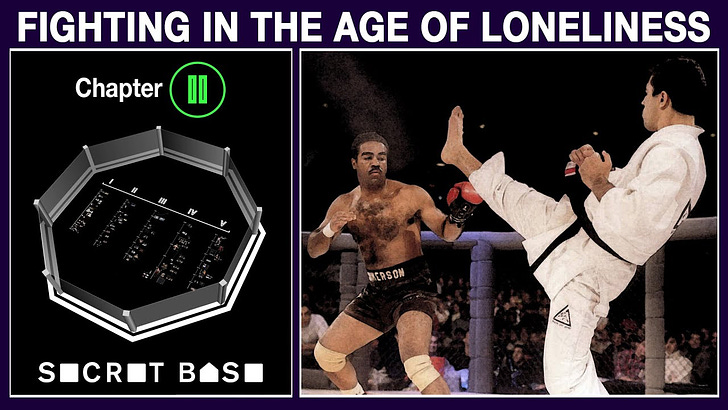

The only thing I knew about mixed martial arts before this week was a video clip I unwittingly watched years ago of a fighter breaking his leg in the octagon. Since seeing that, my interest in learning more about the sport has held steady at zero. But I’ve enjoyed Jon Bois’ stats-nerd videos for SB Nation so much that I was willing to take a flyer on “Fighting in the Age of Loneliness,” a five-part MMA history on YouTube he coproduced. I don’t entirely buy the thesis that the sport’s rise is a function of America’s dark collective id emerging in the wake of three decades of social fragmentation, economic decline, and cynical politics. (UFC can’t be both our way of acting out against peace-dividend ennui and our post-9/11 proxy warrior, and if it can, then so what? Maybe just say America has always been violent.) But I don’t mind having this stuff contextualized either, and by the second episode I was moved to…not watch MMA, but at least watch the rest of the series. I’ve enjoyed “Fighting…” more than a whole lot of the eat-your-veggies cultural criticism I’ve read this year. This is episode two; no legs get broken (that’s in episode one), though there’s Donald Trump content and somebody gets his ear bitten. (Donald Trump does not bite somebody’s ear.)

Thanks for reading. This was a very manly edition of the newsletter; as ever, I’m working on it. Send correspondence to mathitak@gmail.com. Buy my book. Headshot illustration by Pablo Lobato.